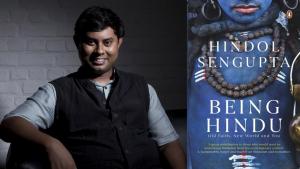

There are few books on Hinduism recently published, authored by practicing Hindus with modern, young, English speaking Hindus as their target audiences and which seek an intimate conversation on the meaning of Hindu identity in the 21st century.

There are indeed some excellent introductory texts on Hindu philosophy and spirituality authored by traditional Hindu monks affiliated to diverse Hindu religious organizations but they are often academically terse and rather nonchalant to those uniquely 21st century concerns which animate young people globally like gender equality, environmentalism or even gay rights (or the lack of it).

In this respect, Sengupta’s work is refreshing for his narrative seeks to present a ‘personal journey in trying to understand what being Hindu means to (him) and many others’. In doing so, Sengupta reminds us of those questions, uncertainties and insecurities which colour our common experiences of being Hindu in the modern world where the power of science and technology is rapidly eroding the apparent necessity of religious faith.

Sengupta complains and rightly that ‘ask most Hindus to explain the principles, history and belief systems of their faith and they would struggle’. Further, ‘How many Hindus really know why they pray? What do the mantras really

mean, and why do they mouth them?’ Sengupta explains such ignorance as outcome generated by the lack of ‘an idea of conversion or spreading of faith by inducting more followers’. It is a careless and flawed explanation and invites more questions than answers it is supposed to generate. For instance, to increase dharmic literacy, the first step should be the easy availability of dharmic or religious education.

Since Independent India adopted a secular constitution, it rejected any semblance of dharmic education in school curriculum of government funded institutions. Previously, over 800 years of Islamic and British colonialism had severely undermined native Hindu educational systems and institutions and the absolute denial of state support eliminated hopes of their revival post-independence. Secondly, school level social science textbooks authored by left wing intellectuals and Marxists with their negative and condescending representation of Hindu beliefs and practices also contributed further to the alienation of a generation of Hindu from their religious and spiritual roots.

It is for this reason perhaps that Sengupta quite justifiably dedicates the first two chapters of his book on affirming ‘the idea of a unified, cultural homeland called Bharat…which existed for almost 3000 years although it could be much older’ and how ‘it is pre-Islamic India that laid the philosophical bedrock for the syncretic, composite culture that India has been able to build (through) the Hindu imagination of a tolerant geography…’, facts which are conspicuous by their absence in most mainstream Indian History textbooks for school students.

In all, the Hindu civilization is probably experiencing a collective crisis of dharmic illiteracy, hitherto unmatched in its hoary history although paradoxically never in its history did Hindu organizations since Swami Vivekananda’s journey to the West have so many spiritual outreach programs.

In his exploration of Hindu beliefs and values, Sengupta seeks to discover virtues which ‘India’s Hindu civilization can offer in the twenty first century’. He supports his insights with the wisdom of thinkers, both eastern and western but dominated by the ideas of Swami Vivekananda, the late nineteenth century Hindu monk who established Hinduism as a world religion through his representation against all odds in the parliament of religions in Chicago, 1893.

In a world where increasing religious fundamentalism is threatening liberties which were taken for granted, Sengupta discovers being Hindu in allowing people to be ‘set free’ upon their individual ‘spiritual journeys’. Unlike Islam or Christianity which seek truth from a supposedly unique historical event, revealed to a single and last prophet and recorded as an unalterable truth until the day of judgment in contrast in Hinduism the key to enlightenment is seeking the ‘truth within’ and discover the truth of Vedic revelation which is an infinite ‘inexhaustible process ‘himself for each man is potentially a prophet, nay, potentially divine.

The consequence of the diverse and liberal Hindu spiritual worldview where there is no single founder, prophet, book or theological position is an absence of the concept of irredeemable sin, eternal damnation, blasphemy and infidel. Sengupta pleads considering just ‘How many millions could and would be saved if the concept of infidel be wiped out? What if were to agree that there are no unbelievers? Would that not be the single greatest act of conflict resolution in the history of the world?’

In an age of intolerance, both real and imagined, Sengupta affirms the validity of Hindu tolerance as its greatest achievement rooted in its ‘lack of theological arrogance’ implicit in its ‘recognition that our way is not the only way’ – a sublime ‘nonjudgmental, nondiscriminatory approach’. Moreover, since Hinduism distinguishes between that which is eternal (sruti) and that which is ephemeral (smriti), it avoids confrontations on adherence to customs and laws unlike orthodox Islamism and associated Sharia.

How alien is the idea of fundamentalism to the Hindu way of life even among its extremist proponents is dramatically illustrated in Sengupta’s reading of Godse’s trial address where Godse, the assassin of Gandhi, expresses his ideological support for a secular Indian state with joint electorates for both Hindus and Muslims.

The possibility that science and religion can not only co-exist but grow symbiotically may sound ridiculous when going through accounts of Western History where pioneering scientists like Galileo and Copernicus were persecuted by the Church. In contemporary times, teaching evolution in schools in America has become controversial thanks to pseudo-scienticic intelligence design theories which seek to save a place for God in the universe, and Christian moral worldviews which hinder stem cell research in certain Western nations. Sengupta persuasively argues that science and Hinduism have never been really in conflict since the Hindu worldview accepts uncertainty and doubt unlike Islam or Christianity.

To exemplify, Sengupta shows that unlike the Christian and Islamic account of Genesis with a sense of finality, the agnostic flavor of the Nasadiya Sukta in the Rig Veda provides opportunities for evolving interpretations. In effect, Sengupta understands the Hindu position resonating with that of the philosopher and scientist, Alan Lightman who explained faith as the ‘willingness to give ourselves over at times, to things, we do not fully understand’. The scientific approach to religion which Vivekananda propounded to the world as being the ‘realization of God’ through specific spiritual pursuits is highlighted here.

Sengupta also commentates on social issues especially those which have over the vicissitudes of times become divorced from what he deems as the original Hindu attitudes towards them. He alludes to the Hindu fable of Ardhanarisiva and suggests that Hinduism does not discriminate against homosexuals whatsoever unlike some other religions and British era legislation in place needs to be reworked which should account for liberal Hindu attitudes on the subject.

In a peculiarly titled chapter ‘Does being Hindu mean you are vegetarian’, Sengupta is quite unconvincing since he merely regurgitates Vivekananda’s views on the subject without reading him in context. Sengupta is unaware that irrespective of the place of meat eating in ancient India, it is a fact that abstinence from meat eating was deemed spiritually rewarding around the age of the Smritis (see, Manu Smriti 5.56 for instance where Manu compares meat eating with carnal delights whose experience was not deemed sinful but whose abstinence was believed to entail great rewards).

Early notions of vegetarianism reached Europe from India through Greeks and much later through European traders in the 16th century. Some religious denominations like the Vaishnavs have always been vegetarian. In contemporary India, almost 40% are exclusively vegetarian while even among non-vegetarians practice of weekly abstinence from meat is quite common. Vegetarianism like Yoga is Hinduism’s gift to the world, and whether derived ritually or ethically, as an outcome vegetarianism especially absence of beef eating offers to make the world a better place by reducing greenhouse emissions and promoting healthier living.

Similarly, Sengupta complains in the same vein about dirty rivers and unsanitary temples. Yet, he evades the fact that industrial pollutants are largely responsible for the condition of our rivers. Similarly, the administration and finances of several Hindu temples are under the management of government controlled temple boards. The inefficiency and maladministration of successive “secular” congress governments and those by like-minded parties united against “Hindu communalism” are squarely responsible for what is wrong with our rivers and temples rather than alleged Hindu social apathy. One could argue that it is Hindu political apathy which is to blame for lack of development, poverty.

Sengupta is offended by the noise of popular Hinduism, ‘For years, my personel quarrel with the commonly seen mass version of Hinduism was how bereft of silence it is. I live in the city of Delhi where inevitably someone or the other organizes a jagran in the neighbourhood’. Quite curiously, in the same city, it is striking that he never encounters the peaceful azaan from some neighbourhood mosque, dawn to dusk, five times a day, everyday.

Sengupta’s attitudes towards rituals is also utterly patronizing, a mere “crutch” until it can be discarded into the dustbin of history. Such reductionisms are dangerous since rituals in Hinduism not only are humankind’s efforts in partaking in the cosmic play of the lord, the divine leela but also the only means for most to overcome the fear of cosmic insignificance. The way of advaita may be intellectually attractive but its goal, the state of nondual consciousness is largely unattainable.

Not without reason did Ramakrishna Paramhamsa affirm the necessity of Bhakti in the age of Kali, nor did Shankara become a composer of some splendid Bhakti poetry like the Bhaja Govindam during his later years. Ultimately, in the absence of theology and ritual, the notion of Hinduism could well be replaced by Buddhism for a modern Hindu since that would also disencumber us of the bogey of caste tyranny.

Sengupta is further out of depth while wading on the controversy of temple destruction by Muslim rulers (and not just invaders) in medieval India. Sengupta agrees that there has been temple iconoclasm but believes such “violent incidents” are balanced by our “composite culture” as reflected in the acts of Akbar and Dara Shukoh, although he is presumably against the white washing of such incidents from our history texts.

The fact remains there is overwhelming archaeological, epigraphical and literary evidences which prove that thousand Hindu temples were destroyed by Muslim invaders and also rulers. Forcible conversion and slave trade are also sad facts of medieval Indian History. Under such circumstances, failed attempts at rapprochement as exemplified in the tragic efforts of Shukoh who was tortured and murdered by Aurangzeb hardly provides a genuine sense of closure which Sengupta implores for us to find.

In a lengthy prologue, Sengupta after showcasing his impeccable ‘secular’ credentials – educated in a convent, revels in Sufi poetry and loves Christian chapel songs expresses his growing concern at how Hinduism had acquired in many minds an ‘ultra-militant edge’ and how this was facilitated by ‘fundamentalist Hindu fringe organizations’. In the end of the book, Sengupta proclaims that the only alternative to prevent such catastrophe was for Hindus to ‘aggressively proclaim that to be Hindu is to shun bigotry, to accept diversity, embrace differences, respect gender rights and actively adopt new technologies and sciences’.

Yet, it is unclear which Hindu Sengupta intends to address. Does he speak to the Hindu in Pakistan who face forcible conversion? Does he speak to the Hindus in Bangladesh who experience everyday discrimination? Does he speak to the Kashmiri Hindus rendered as refugees in their homeland? Does he speak to those extremist Hindus of India who actively resist proselytizing activities?

Sengupta could probably ponder over this episode from Swami Vivekananda’s life-

…in the course of a conversation with a disciple in Calcutta, (Vivekananda) asked, ‘What would you do if someone insulted your mother?’ The disciple answered, ‘I would fall upon him, sir, and teach him a good lesson.’

‘Bravo!’ said the Swami. ‘Now, if you had the same positive feeling for your religion, your true mother, you could never see any Hindu brother converted to Christianity. Yet you see this occurring every day, and you are quite indifferent. Where is your faith? Where is your patriotism? Every day Christian missionaries abuse Hinduism to your face, and yet how many are there amongst you whose blood boils with righteous indignation and who will stand up in its defense?’…..

(Source: Vivekananda: a biography, Swami Nikhilananda)

Sometimes, it isn’t about being Hindu but staying Hindu in an increasingly intolerant world.

(This is a review of the book, Being Hindu, reprinted with courtesy to reviewer Saurav Basu and the magazine Swarajya, where it first appeared).