Samaresh Basu wrote Amrita Kumbher Sandhaney in 1954, India was seven years old as an independent nation and still smarting from the pains of the bloody separation.

Basu did not visit Allahabad, the venue of the Kumbh Mela, to propitiate the Gods, he was not seeking one. His was not a pilgrimage in the real sense. He wanted to be at the heart of what eventually became the world’s largest religious gathering.

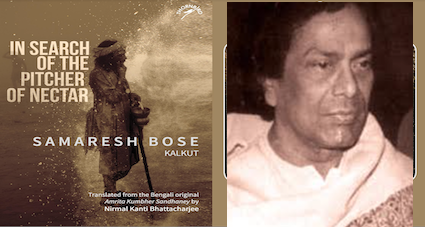

His classic has been translated as In Search of the Pitcher of Nectar by Nirmal Kanti Bhattacharjee, an accomplished author, and plugged on the stands by Niyogi Books. Was the book translated from Bengali before? I do not know, it’s been 68 long years. But this one looks impressive.

Basu was young, he was a learner.

Basu wanted to meet the faithfuls who visit the Kumbh Mela to wash away their sins and bath in the sacred confluence, where the Ganges and Yamuna rivers converge with the invisible and mythic tributary known as the Saraswati. The bath, Hindus believe, brings salvation from the cycle of life and death.

Kumbh Mela has its roots in a Hindu tradition that says God Vishnu wrested a golden pot containing the nectar of immortality from demons. And then, in the battle gods won. In the 12-day fight for possession, four drops fell to earth, in the cities of Allahabad (now Prayagraj), Haridwar, Ujjain and Nasik, who share the Kumbh as a result.

Basu travelled in a third class train compartment from Calcutta (not Kolkata then) and had soldiers of the Indian army and Marwari families as company. He talked on the way as the train – I presume it was a coal-driven engine that pulled the coaches – sped out of Calcutta.

Basu was keen to find why millions visit the Kumbh Mela. Was it for Moksha? Or to find a lost brother, or a lost sister? Probably Basu knew getting separated at the Kumbh Mela and reuniting miraculously decades later has always been a common storyline in Indian cinema, especially Bollywood. Friends had told him, Basu also saw at the congregation loudspeakers blaring: “Do not forget to take the injection for cholera; you have to obtain the certificate after taking the injection. Without the certificate your entry to the mela is not permitted.”

Many got the certificates, many didn’t, and wept inconsolably at the entrance of the mela, Basu chronicled their stories.

Basu remembered what he had written while sitting in the train: “I do not know if they are blinded by faith, but I am going to see the gathering of people. Our desire for other things may be satiated, but the desire to see and taste humankind is insatiable. What is more strange than humankind in this world?”

Basu walked into the million and realised how comprehension was also an issue, India is home to 22 major languages and hundreds of dialects. Sign languages, saw Basu, worked brilliantly at the Kumbh Mela. Wrote Basu: “Blinded by faith! If lakhs of people are blinded by faith, then why not search for the reason? What is that celestial blinker that can blind lakhs of eyes.”

The book, which he wrote under the pseudonym of Kalkut, is a human document set off on his unique journey to understand the life and times of Indians blinded by their belief that they could wash away their sins after just one wash in a river that turns sacred for a handful of days.

In gripping chapters, Basu – along with a host of characters – turns the book into a sequence of dramatic events. His protagonists are mostly poor and oppressed from every corner of India. The book reads like a travelogue through the analytical scepticism of his socio-political beliefs. It’s a brilliant book, we need to remember Basu was less than 30 years-old when he wrote this deeply moving human document.

Basu weaves the novel through some of the unique characters at the mela. There is Shyama, there is Balaram, there is Prahlad and ever-smiling Didima that translates into maternal grandmother. Basu was not chronicling the times at Kumbh Mela but I would say the author emerges In Search of the Pitcher of Nectar as a sensitive observer of political and social changes he witnessed at the huge human congegration.

Basu met sadhus, synonymous with long, white bread and naked, skeletal frames who called two of the rivers worldly, the third divine. For years, the sadhus have been the primary attraction at the festival, setting up tents to greet the faithful. Basu walked into their tent, talked about life and after-life. He met the naga sadhus, holy men who have renounced all material possessions including clothing. Basu sat with them around fires and got lessons on the Hindu faith, and saw the Nagas smoking marijuana.

Basu did not mind spending time in smoke-filled tents.

The book details how millions worshipped different gods and yet did not claim exclusivity or superiority, never condemn anyone. Basu was majorly impressed by this unity in multiplicity. He says time and again in the book that it is the main theme in Hinduism that binds Indians together. For Basu, the vessel containing divine nectar remained elusive but what impressed him was the enormousness of the vast festival drawing multitudes of Hindu ascetics, ordinary devotees, celebrities, tourists and even royalty.

Spirituality, politics and tourism, everything impressed Basu. A whole new world opened in front of his eyes in the cacophony and chaos of the vast religious festival.

Today, Unesco has recognised Kumbh Mela as an intangible cultural heritage. Not when Basu passed through the sand-filled banks of the Sangam in Allahabad looking for the sacred pitcher containing the nectar of immortality. Those were different times, difficult times. Pick up a copy, read it, and bask in the big, human confluence of religion and love, prayers and faith.

(Shantanu Guha Ray, a Wharton-trained journalist, is the Asia Editor of Central European News & Zenger News and an award-winning author. He won the 2018 Crossword award for his book, Target, which probed the NSEL payment crisis.)