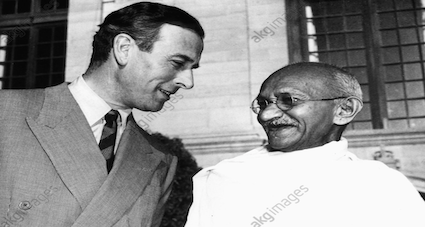

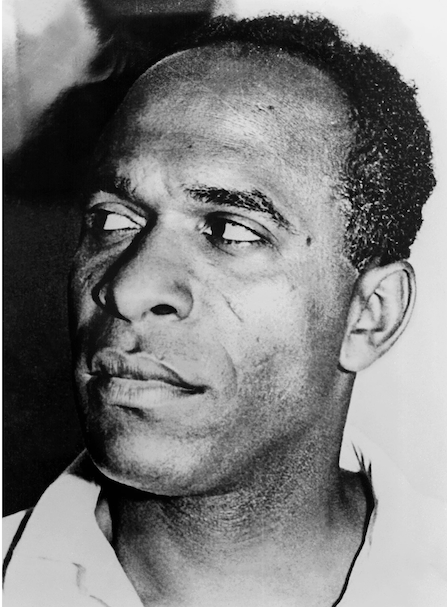

It always troubled me how a global empire so ruthlessly built as the British did, bowed to the moral powers of Mahatma Gandhi. I then hit upon “The Wretched of the Earth” by Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) who lived only 36 years but his insight on colonialism inspires African nationalists to this day.

This passage below in the book literally transposes the history of India from the founding days of Congress, Gandhi’s return in 1915, and how our “freedom movement” hung out “militants” like Subhas Chandra Bose or “nationalist” Sardar Patel to dry.

Were millions of Indians fooled? Are they being fooled to this day in reverence to our original heroes?

Read on and make your own call….

From “The Wretched Of The Earth”

“Capitalism, in its expansionist phase, regarded the colonies as a source of raw materials which once processed could be unloaded on the European market.

After a phase of capital accumulation, capitalism modified its notion of profitability. The colonies become a market. The colonial population a consumer market. Consequently, if the colony has to be constantly garrisoned, if trade slumps, in other words if manufactured and industrial goods can no longer be exported, this is proof that the military solution must be ruled out.

A blind domination on the model of slavery is not economically profitable for the metropolis (of colonial masters). The monopolistic fraction of the metropolitan bourgeoisie will not support a government whose policy is based solely on the power of arms. What the metropolitan financiers and industrialists expect is not the devastation of the colonial population but the protection of their “legitimate interests” using economic agreements.

The crackdown against a rebel sultan is “is a thing of the past. Matters have become more subtle, less bloody; plans are quietly made to eliminate the Castro regime. Guinea is held in a stranglehold, Mossadegh is liquidated.

The national leader who is afraid of violence is very much mistaken if he thinks colonialism will “slaughter us all.” The military, of course, continue to play tin soldiers dating back to the conquest, but the financial interests soon bring them back to earth.

The moderate nationalist political parties are therefore requested to clearly articulate their claims and to calmly and dispassionately seek a solution with the colonialist partner respecting the interests of both sides.

When this nationalist reformist movement, often a caricature of trade unionism, decides to act, it does so using extremely peaceful methods: organizing work stoppages in the few factories located in the towns, mass demonstrations to cheer a leader, and a boycott of the buses or imported commodities. All these methods not only put pressure on the colonial authorities but also allow the people to let off steam.

This hibernation therapy, this hypnotherapy of the people, sometimes succeeds. From the negotiating table emerges then the political agenda that authorizes Monsieur M’ba, president of the Republic of Gabon, to very solemnly declare on his arrival for an official visit to Paris: “Gabon is an independent country, but nothing has changed between Gabon and France, the status quo continues.” In fact the only change is that Monsieur M’ba is president of the Republic of Gabon, and he is the guest of the president of the French Republic.

The colonialist bourgeoisie is aided and abetted in the pacification of the colonized by the inescapable powers of religion. All the saints who turned the other cheek, who forgave those who trespassed against them, who, without flinching, were spat upon and insulted, are championed and shown as an example.

The elite of the colonized countries, those emancipated slaves, once they are at the head of the movement, inevitably end up producing an ersatz struggle.

They use the term slavery of their brothers to shame the slave drivers or to provide their oppressors’ financial competitors with an ideology of insipid humanitarianism.

Never in fact do they actually appeal to the slaves, never do they actually mobilize them. On the contrary, at the moment of truth—for them, the lie —they brandish the threat of mass mobilization as a decisive weapon that would as if by magic put “an end to the colonial regime.”

There are revolutionaries obviously within these political parties, among the cadres, who deliberately turn their backs on the farce of national independence. But their speeches, their initiatives, and their angry outbursts very soon antagonize the party machine. These factions are gradually isolated, then removed altogether.

At the same time, as if there were a dialectical concomitance, the colonial police swoops down upon them. Hounded in the towns, shunned by the militants, rejected by the party leaders, these undesirables with their inflammatory attitude end up in the countryside.

In their speeches, the political leaders “name” the nation. The demands of the colonized are thus formulated. But there is no substance, there is no political and social agenda. There is a vague form of national framework, what might be termed a minimal demand. The politicians who make the speeches, who write in the nationalist press, raise the people’s hopes. They avoid subversion but in fact stir up subversive feelings in the consciousness of their listeners or readers. Often the national or ethnic language is used. Here again, expectations are raised and the imagination is allowed to roam outside the colonial order.

Then the political leader summons the people to a meeting, there could be said to be blood in the air. Yet very often the leader is mainly preoccupied with a “show” of force—so as not to use it. The excitement that is fostered, however—the comings and goings, the speech making, the crowds, the police presence, the military might, the arrests and the deportation of leaders—all this agitation gives the people the impression the time has come for them to do something. During these times of unrest the political parties multiply the calls for calm to the left, while to the right they search the horizon endeavouring to decipher the liberal intentions of the colonial authorities.

“From the moment national consciousness reaches an embryonic stage of development, it is reinforced by the bloodbath in the colonies which signifies that between oppressors and oppressed, force is the only solution. We should point out here that it is not the political parties who called for the armed insurrection or organized it. All these perpetrations of repression, all these acts committed out of fear, are not what the leaders wanted. These events catch them off guard.

It is then that the colonial authorities may decide to arrest the nationalist leaders. But nowadays the governments of colonialist countries know perfectly well that it is highly dangerous to deprive the masses of their leader. For it is then that the people hurl themselves headlong into jacqueries, mutinies and “bestial murders.” The masses give free rein to their “bloodthirsty instincts” and demand the liberation of their leaders whose difficult job it will be to restore law and order. The colonized who spontaneously invested their violence in the colossal task of destroying the colonial system soon find themselves chanting the passive, sterile slogan: “Free X or Y!” The colonial authorities then free these men and start negotiating. The time for dancing in the streets has arrived.

“In other cases, the political party apparatus may remain intact But in the interplay of colonial repression and the spontaneous reaction by the people, the parties find themselves outmaneuvered by their militants. The violence of the masses is pitted against the occupier’s military forces; the situation deteriorates and festers. The leaders still at liberty are left on the sidelines. Suddenly rendered helpless with their bureaucracy and their reason-based agenda, they can be seen attempting the supreme imposture of a rearguard action by “speaking in the name of the muzzled nation.” As a general rule, the colonial authorities jump at this piece of good fortune, transform these useless characters into spokesmen, and, in next to no time, grant them independence, leaving it up to them to restore law and order.

But it is common knowledge that for 95 percent of the population in developing countries, independence has not brought any immediate change. Any observer with a keen eye is aware of a kind of latent discontent which like glowing embers constantly threatens to flare up again.

So they say the colonized want to move too fast. Let us never forget that it wasn’t such a long time ago the colonized were accused of being too slow, lazy, and fatalistic.

The nationalist leaders know that international opinion is forged solely by the Western press….

Frantz Fanon (above)

(Very few lines or sentences have been left out in the above passage in order to retain brevity—NewsBred)