Overnight, I received a fair amount of responses to the previous article on the subject of the Farm Bills 2020 in India, and my references to Kolkata therein.

As far as Kolkata is concerned, I grew up and still frequently visit the city of Abdul’s Girlfriend, Victoria, quite often. The surname helps. As well as a maritime heritage and friendships therein.

Pertaining to the Farm Bill of 2020, my simple question right back, rhetoric is a skillset that is very important when trying to learn as well as get your point across, is simply this –

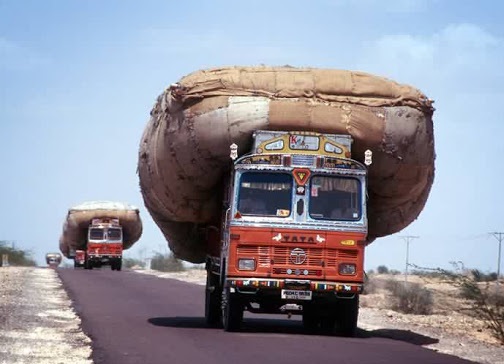

How many journalists, opinion makers, politicians, society leaders, PR persons, lobbyists and similar “types” including hi-fi “agriculturists for zero taxation” have actually physically moved agri produce of any sort from farm to fork? In their lifetime, by road, in India?

xxx

1967 around Dussehra. We were returning from a family trip which involved my father also headed for a location “beyond Chakrata” so we went in the family car up to Mussoorie and stayed at the Savoy while my father went further into the mountains in another accompanying civilian vehicle which even then you could make out was visibly “attached”.

Please feel free to do your 2+2 but the real story has to do with how on the return trip our car, being driven by my father, was well over-loaded with family of 4 children plus my mother, a few sacks full of wheat purchased from his colleague’s farm en route, and then to add to the joy, an overhead carrier which was extremely high on Centre-of-Gravity with our luggage as well as sacks full of “gud” (jaggery) with which we were going to make traditional “patt ke laddoos” when we returned to Delhi.

(The version my family made was a half-way point between a “pinni” and a “gaund ke laddoo” but with a layer of sweetened wheat flour shakar-paras rolled into them, thus the word “patt” for reasons I do not recall. Somebody from Jhung-Meghiana may know?

The “attached” car had fallen behind for whatever reason, it had already become dark, and somewhere between Muzzafarnagar and Meerut we were stopped for “checking”. The trusty Ambassador was down on the springs and the sacks of wheat as well as jaggery were duly objected to by the Law. Matters got resolved a few minutes later when the “attached” car landed up but that was, and I was all of 11 then, the second time I learnt how dangerous it was to move agri-produce of any sort in India. Unless your father was around with a restricted bore but licenced .38 visible under his bush-shirt.

The first time was when I was all of 8, and rode a tractor-trolley combo loaded with purple radish from the farms of relatives in Rohtak to the mandi in Hissar, and observed how the complete transactions en route were conducted. Probably 5% of the cargo was removed as we progressed by a succession of checking staff and then the mandi itself was another revelation. This was despite my uncle carting a licenced shot-gun around with him, loaded in both barrels and cocked – very soon thereafter the said Uncle was killed in a fight over land by people carrying pitchforks used extensively after he had fired both barrels.

These two experiences, in 1964 and then 1967, ensured that farming was not going to be one of the choices for me, others in my family rural and urban, and probably many more, in India.

Why would you want to make an effort to do well in a profession where anybody and everybody on the road could stop you, check you, loot you and deprive you of your self-respect, sometimes your life, assuming that the weather Gods had been kind and that you did have a crop to go to market with in the first case?

xxx

I joined the Merchant Navy in 1973 and for the first few years I worked on ships which were solely engaged in transporting food grain to India from the US, Canada and Australia. I also saw how agri-produce of all sorts, perishable, live on hoof, refrigerated and dry, all moved seamlessly across not just local “borders”, but internationally.

xxx

I returned home to Delhi on very short leave in July-August 1976, signing off in Vizag, and reached Delhi via Hyderabad and Bombay by air and thence from Bombay to Delhi by train. In Mumbai, I picked up four wooden cases of Alphonso Mangoes, and with the help of the Railway father of a friend. got them loaded into the brake-van, along with a motor-cycle as well as my own luggage. In my hand baggage were some felt pens, a portable Olivetti typewriter, “foreign” toiletries, and three tins of powdered chocolate – requisitioned by my younger sister.

At Delhi, my “foreign looking” suitcase (I still have it!), the cases of mangoes and the motorcycle marked me for “checking”. Having been a shippie for a while by then, and still in my teens, I think I handled the situation admirably and ended up parting with one case of mangoes as well as one tin of powdered chocolate and many crisp 10/- notes. They were simply not interested in the felt pens or the portable type-writer.

xxx

I was now, probably, ready for a career ashore in logistics – especially of all sorts of agri-produce, I just didn’t know it, but the foundations had been laid. My father, however, had let go whatever ancestral rights he had on agricultural land – convinced that none of his offspring were ever going into that line of work.

(To be continued)

Veeresh Malik was a seafarer. And a lot more besides. A decade in facial biometrics, which took him into the world of finance, gaming, preventive defence and money laundering before the subliminal mind management technology blew his brains out. His romance with the media endures since 1994, duly responded by Outlook, among others.

A survivor of two brain-strokes, triggered by a ship explosion in the 70s, Veeresh moved beyond fear decades ago.