The frail figure of Upen Kisku stands right outside a dilapidated cottage where veteran Naxalite leader Kanu Sanyal lived and died. Sanyal hanged himself to death.

It is noon on June 6, 2022, at Seftullajote village near Naxalbari.

The iconic town – the railway station is still named Naksalbari – is 25 kms from dusty and crowded Siliguri, the central transfer point connecting Bhutan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sikkim and Darjeeling and the seven northeastern states.

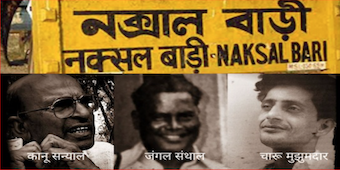

Kisku is the son of Jangal Santhal, a confidant of Sanyal and Charu Mazumdar, Marxist ideologues who triggered an epic class war – the Naxalite movement – in the afternoon of May 24, 1967. A police inspector was killed by an arrow that came from a crowd of farmers protesting against the brutalities of feudal landlords.

The police retaliated the next day, firing on a farmers meeting, killing 11 people, including eight women and two infants.

Close to a government school, there is a red plaque that contains the names of those who died. There are some busts of Maoist leaders perched on red pillars, long considered the ubiquitous symbol of violent revolution. The busts are now surrounded by weeds and grass. Nearby, goats graze in the open, farmers dry wheat on main thoroughfare used by men, women, children and vehicles. Once a year, some 50-odd Marxist supporters visit the statue and pay red salute with clenched fists.

That’s Naxalbari, and the much-vaunted Laal Salaam war cry of the Marxists which is totally lost. In the last assembly elections in 2021, the Left Front did not put up a candidate in Naxalbari, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) candidate Anandamoy Barman swept the polls. It needs a mention here that Amit Shah – then he was the BJP president – had launched the expansion of his party in West Bengal way back in 2017.

Kisku says his parents are dead, he earns a pittance from the tea gardens and local stores, and Naxalbari is his worst dream, actually a nightmare. “No one cares about the poor anymore, no one has time. The poor have become poorer. No one comes to Naxalbari to get a feel of the uprising. Young tribal students have expensive smartphones.”

Only when someone opens up Sanyal’s home for a coat of mud laced with cow dung, Kisku says he sits on the floor and stares at the roof made of corrugated tin. He knows how a recluse Sanyal – battered, bruised and betrayed by fate – hanged himself on March 23, 2010.

Kisku knows the exact spot in the wooden frame where the former court clerk and one of the founder members of the Naxalite movement hanged himself.

“Violence will never eradicate poverty, it never has eradicated poverty,” Kisku sounds philosophical and brutally realistic.

Death toll from Naxalite violence is high in India. Between 2004 to 2021, 8527 people have been killed by Left Wing Extremism in the country, says the Home Affairs Ministry.

In the dark of the night in Naxalbari, wild elephants cross tea gardens, farmers drink country liquor and women do household chores. The affluent crowd the bars, they are all breathing new life to emerge from the shadows of the failed Maoist revolution that continues to be the village’s only calling card.

In the late 60s and early 70s, the story of Naxalbari, the one-road village nestled at the base of cloud-kissed hills, had been one of continued violence, shattered businesses, shrinking classrooms and withering communities. But not any more.

Naxalbari’s 250,000-plus population comprises largely tribal members of a quiet farming community, micro entrepreneurs, employees of departmental stores selling white goods traders and timber merchants.

For them the movement is past, India’s $25 billion e-commerce market is important for them because they have tasted economic growth. The youth are travelling out of the village, taking trains and flights to Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Chennai and picking up jobs in sectors ranging from insurance, finance, trading, infrastructure to tourism, education and agriculture.

“We have many schools, colleges, four shopping malls and three bars,” laughs Abhishek Oraon, a strapping young footballer who calls himself a die hard supporter of Manchester United.

Oraon does not even care that their homeland is still considered the incubator of India’s epic class war. “I was born much after the armed struggle. I am not insensitive to the poor. I studied at the Birsa Munda college at Hatighisa. Hundreds graduate from that college and travel out for jobs. Naxalbari has changed.”

Oraon knows Hatighisa is also home to Sanyal. Six gram panchayats make up the Naxalbari block, all a patchwork of old tea estates.

So what happened out of the movement?

The leading lights of this armed struggle were ultra-left leader Charu Majumdar and his close associates Kanu Sanyal and Jangal Santhal, who planned and mobilised tribals for months before the outbreak of Naxalbari uprising on May 25, 1967.

Majumdar and his associates belonged to the radical stream of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), which was inspired more by Mao Tse Tung’s idea of peasant rebellion than Marx-Lenin’s vision of class war. For the records, the Chinese Communist Party Revolution under Chairman Mao, which achieved a sensational victory over the nationalist government under Chiang Kai-Shek through an armed peasant rebellion in 1949, had left a deep impact on Majumdar and Sanyal.

“The annihilation of class enemies does not only mean liquidating individuals, but also means liquidating the political, social and economic authority of the class enemy,” wrote Majumdar.

Inspired by Mao’s success, Majumdar published his famous Eight Documents in 1965, arguing that the CPI-ML should endorse Mao’s strategy of armed rebellion against the Indian state. Sanyal was not very keen on Majumdar’s strategy.

Soon swathes of land in Bengal turned into what Majumdar called liberated zones.

Word of the Naxalbari movement spread quickly across Bengal and India. The Bengal government responded with brutal force. Many leaders and sympathisers of the movement were killed by the police or disappeared after being arrested. Among them were many bright urban students drawn in by the romance of the revolution. Majumdar went underground in late 1967 and was captured by the Bengal police in July 1972. Majumdar died in police custody 10 days later.

His supporters still believe that he was killed by the police. Everything went up in smoke after Majumdar died, and the West Bengal government brutally crushed the radicals.

The New Naxalbari

Now, growth is the new change in Naxalbari where livelihoods are still tied to the earth, a little over 59 percent connected with agriculture. The National Highway’s six lane road cuts through Naxalbari whose changing skyline is full of shopping malls and grain elevators, motorbike showrooms, departmental stores, designer weddings and Valentine parties. Real estate is at a premium.

The romance of revolution is all but over, says a manager at Siliguri’s most expensive Marriott Bonvoy hotel. “People do not travel to Naxalbari on reaching Bagdogra airport, they go to Darjeeling, Sikkim or Bhutan,” says the manager, who cannot be quoted under company rules.

It is all about choices, access and availability of an emerging, new world. There is no need to fight powerful landlords any more because there are none.

Once, only the rich had electricity, they were considered powerful. Today, every house in Naxalbari has electricity, nearly 75 percent of the villagers are literate, and more than 60 percent of the population is less than 35 years of age, and add tremendous value to North Bengal’s burgeoning economy.

The violent ideology that was once in vogue does not find any political space in Naxalbari, the village is another slice of 21st-century India. The caste-based feudal superstructure that the Naxalbari movement set out to annihilate may exist in some quarters in India but remains diluted, says a local trader. “In a market economy, there is space for competition and growth but no scope for armed struggle and violent deaths.”

Naxalbari’s middle-class is enamoured with India’s rising global status. They have instant answers for everything through their handsets — more powerful than any nuclear weapon — which helps them access the world. Everyone knows how to write and send WhatsApp messages.

This is an interesting demographic shift that has been uniformly welcomed in Naxalbari where once tradition was seen as the central charm of rural life.

Naxalbari is now about life, not protests or deaths anymore. Leaders of the Naxalite movement did not leave behind any legacy for the locals to follow. Residents of Naxalbari, it looks clear, do not wish to retain and continue the legacy of the Maoist foot-soldiers.

These are fresh steps in what was once considered the first, giant step in the great Indian proletariat revolution.

(Shantanu Guha Ray is a Wharton-trained journalist and award-winning author. He lives in Delhi with his wife and two pets. He won the 2018 Crossword award for his book, Target, which probed the NSEL payment crisis.)