There has been a concerted campaign to depict the South China Sea as an indispensable artery for commercial shipping and, therefore, a justifiable object of US attention and meddling.

This flagship of this effort is invoking the “$5 trillion dollars” worth of goods that pass through the SCS each year. Reuters, in particular, is addicted to this formula.

Here’s seven Reuters news stories within the last month containing the $5 trillion figure:

China Says South China Seas militarization depends on threat

China seeks investment for disputed islands, to launch flights

China defends South China Sea reef landings after Vietnam complaint

Philippines files protest against Chin’s test flights in disputed sea

China again lands planes on disputed island in South China Sea: Xinhua

Filipino protestors land on disputed islands in South China Sea

South China Sea tensions surge as China lands plane on artificial island

What interests me is that these seven articles reflect the work of six reporters and seven editors (seven to six! Glad to see Reuters has a handle on the key ratios!) in five bureaus and they all include the same stock phrase. How’s that work? Does headquarters issue a ukaz that all articles about the South China Sea must include the magic $5 trillion phrase? Does the copyediting program flag every reference to the South China Sea omitting the figure? Or did the reportorial hive mind linking Beijing, Manila, Hanoi, Hong Kong, and Sydney spontaneously and unanimously decided that “$5 trillion” is an indispensable accessory for South China Sea reporting?

I guess it’s understandable. A more accurate characterization of the South China Sea as “a useful but not indispensable waterway for world shipping whose commercial importance, when properly exaggerated, provides a pretext for the United States to meddle in Southeast Asian affairs at the PRC’s expense” is excessively verbose and fails to convey a sense of urgency.

The kicker, of course, is that the lion’s share of the $5 trillion is China trade, and most of the balance passes through the South China Sea by choice and not by necessity.

In other words, the only major power with a vital strategic interest in Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea is the People’s Republic of China. And the powers actually interested in impeding Freedom of Navigation down there are…pretty much everybody else, led by the United States.

Let’s look at Marine Traffic, a most interesting website which offers dynamic real time ship information and some useful historical data free of charge, and provides an idea of the actual shipping patterns in the region.

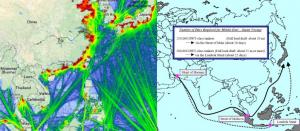

If you select the “density map” option and zoom in, you get this view of the busiest shipping routes (green lines) and busiest ports (red blobs) in and around the South China Sea (view the left picture with this article).

Note that marine traffic in the South China Sea does a few things. First of all, much of it goes, unsurprisingly, to the Peoples Republic of China. Second, except when friendship-building volleyball games in the middle of the SCS are on the agenda, Vietnam, Indonesia, Taiwan, and the Philippines are largely served by coast-hugging routes outside the PRC’s dreaded Nine-Dash-Line.

Third, the rest of the traffic that transits the SCS pretty much on a straight line is headed for Japan and South Korea. This would seem to support the perception that Japan and South Korea, our precious allies, need protection against threats to their supply of hydrocarbon-based joy juice, their economies, indeed their national security and ways of life emanating from the overbearing PRC presence on the South China Sea lifeline.

Not quite.

The strategic insignificance of the South China Sea to Japan and the Republic of Korea has been well known since the 1990s, when “energy security” became an explicit preoccupation of Japanese planners.

Here is an insightful passage from a book by Euan Graham, Japan’s Sea Lane Security: A Matter of Life and Death?, published in 2005.

The cost to Japan of a 12-month closure of the South China Sea, diverting oil tankers via the Lombok Strait and east of the Philippines, has been estimated at $200 million…The volume of oil shipped to Japan from the Middle East is evenly split between Lombok and the Straits of Malacca…

Here’s a nice map (the right image) showing the Lombok route, also mentioning the only difference with Malacca—two more days in sailing time over 20 days for the straight shot through the South China Sea. Also note, as this graphic does, that the biggest crude carriers, 300,000 DWT and up, can only take the Lombok route.

What does two extra days on the water mean? Per Graham,

…Based on an oil import bill of $35 billion in 1997, [a cost of $88 million for diverting through Lombok] accounts for 0.3% of the total.

So is Japan going to light off World War III to keep the purportedly vital SCS SLOC open and save 1% on its oil bill?

Here’s one fellow who doesn’t think so:

CSD [Collective Self Defense] will not allow minesweeping ops in SCS/Malacca Strait as unlike Hormuz there are alternative routes.

That’s a statement that notorious appeaser, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, made in the Diet, as reported on Corey Wallace’s Twitter feed.

Republic of Korea: imports less than 1 billion barrels per annum. Cost of the Lombok detour: maybe $270 million.

Bottom line, everybody prefers to use Malacca/South China Sea to get from the Persian Gulf to Japan and South Korea. It’s the straightest, it’s the cheapest, there’s Singapore, and, in fact, shipowners looked at the economics and decided to dial back the construction of “postMalaccamax VLCCs” (Very Large Crude Carriers) so they’d always have the option of going through the Malacca Strait and South China Sea.

But if that route goes blooey, they can always go via Lombok and the Makassar Sea. Just a little bit more expensive.

So, the South China Sea is not a critical sea lane for US’ primary North Asian allies Japan and the Republic of Korea.

What about the threat to the Antipodes? Core ally Australia? If the PRC shut down the South China Sea, what would that do to Australian exports (other than to China, naturally)?

From Euan Graham’s volume quoted above:

Iron ore and coke shipments from Australia account for most of the cargo moved through the Lombok Strait…Lombok remains the principal route for bulk carriers sailing from Western Australia to Japan.

They use Lombok already!

It should be clear by now that the South China Sea as a commercial artery matters a heck of a lot more to…China, unsurprisingly, than it does to Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the United States.

Here’s the funny thing. The South China Sea is becoming less and less important to the PRC as well, as it constructs alternate networks of ports, pipelines, and energy assets.

The idea that the PRC will ever wriggle free of the maritime chokehold is anathema to the US Navy, which has staked its reputation, claims to a central geo-strategic role, and budget demands on the idea that the US Navy’s threat to the PRC’s seaborne energy imports is the decisive factor that will keep the Commies in their place.

Indeed, Middle Eastern oil, oil that at the very least leaves the Middle East by ship, is probably going to be a big deal in China for decades. But the PRC is trying to do something about it in reckless disregard of the friendly and disinterested advice of the US Navy.

The Belt and Road initiative of China is creating a lot of new channels to move energy and goods in and out of the PRC that don’t rely on the South China Sea.

While you’re at it, find the Andaman Sea. It’s between Burma and India, to the west of the South China Sea and Malacca Strait. The PRC has already built a terminal at Maday in Burma’s Rakhine State and twinned oil and gas pipelines to Kunming in China to, “bypass the Malacca trap’.

And for container shipment, the PRC apparently plans to jog the highspeed railway it’s building to Bangkok over to a new deep sea port down the coast from Maday in Burma at Dawei (instead of pursuing the perennial Thai pipe dream of the Kra Canal across the isthmus separating the Andaman Sea from the Gulf of Thailand).

Also check out Gwadar. The PRC has made a commitment to invest tens of billions in the Pakistani insurrectionary, logistical, and geopolitical nightmare that is the Boondoggle in Balochistan with the prospect of sending oil and gas over the Himalayas to give provide another option for avoiding the South China Sea.

Pipelines are, of course, more expensive to operate and vulnerable to attack by local insurgents and more mysterious forces, as US strategists are suspiciously keen to point out. Ports in third countries are liable to meddling by pro-US governments, factions, and regional proxies. But the PRC is building ‘em. If the US can spend half a trillion dollars on our national security, the PRC is also willing to gamble a couple hundred billion on its energy security in defense and capital budgets (and enrich deserving PRC contractors) and bear the added operating expense of moving oil & gas from A to B not through the Malacca Strait.

Which means, of course, it’s time to hype that PRC threat to the Indian Ocean!

As these massive and risky alternative expenditures by the PRC—and the complete absence of plausible threats to Japan, South Korea, and Australia interests—indicate, the only genuine role the South China Sea played as a strategic chokepoint worthy of US interest is…against the PRC.

Bad news is, with the PRC putting its energy eggs in a multiplicity of baskets, if it ever comes to fighting the real war with China—a full-fledged campaign to strangle it by cutting off its energy imports (like we did with Japan in the 1930s! Hey! Useful historical analogy)—we’ll have to do it in a lot of places, like Burma, the Indian Ocean, and Djibouti, as well as the South China Sea. A real world war!

Good news is, as the PRC’s shipping options increase, the strategic importance of each individual channel decreases…as does the desire of the PRC, Japan, ROK, or Australia to risk regional peace for an increasingly irrelevant sideshow—and the local interests of Vietnam and the Philippines–diminishes.

What I hope is that the South China Sea, instead of serving as the flashpoint for World War III, may well end up as a stage for imperial kabuki as the US & PRC bluster and posture to demonstrate resolve to their neighbors and allies…and an opportunity for political posturing, amped-up defense spending, and plenty of opportunities for the hottest of media and think-tank hot takes.

That would keep everybody happy.

This piece by Peter Lee has appeared in Unz Review and NewsBred gratefully acknowledges the source of this content.