There were men, women and children, thousands of them, bursting through gates of the Bhopal railway platform, emitting a tornado of wails, the crushing pressure dropping them over each other on railway tracks, rising, grabbing and swinging on the doors of my parked train, lunging at the iron rods of my window with a ferocity which threw a startled me deep into my compartment, now swaying like a leaf under the impact.

I was 20, returning from Mumbai, what we once called Bombay, onwards to my ancestral town Lucknow and the train had met its scheduled stop-over in Bhopal, almost midway through the journey. It was early hours of December 3, 1984 and all I could put it to was some sort of riot unfolding, an eye-witness account I would share with my people back home next morning.

Decades of mornings have passed since then, anniversary after anniversary, deaths after deaths, yet history’s biggest industrial disaster, the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, is still unfolding after it consumed 20,000 lives due to poisoned air of that night which escaped a chemical plant in the heart of the city. How do I look back when something new has happened all along in these 35 years?

Do I start with that terrible night when tonnes of cyanide-gas burst through the rusted tanks and broken pipes of a chemical plant in Bhopal, owned by then one of West’ poster-boy of a multinational, Union Carbide; the poison that smelled like boiled cabbage enveloping the cluster of slums which had sprang up around the factory in the need for a living. Thousands of poor and unprotected rushed out howling deep in the night, blinded in eyes, choked in throats, lungs which would burst within next few hours.

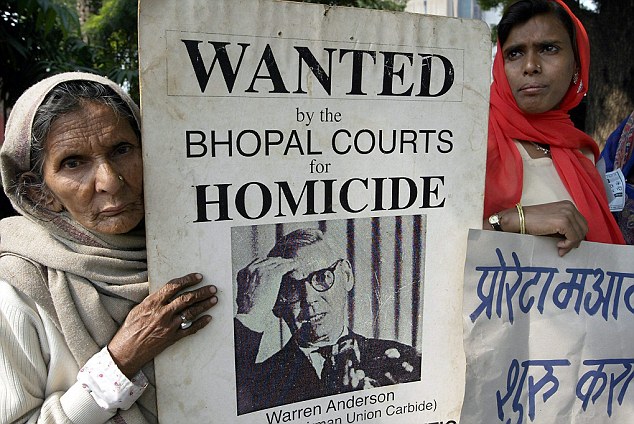

Do I stop and narrate how an enterprising local journalist had seen it coming three years in advance to the tragedy, his warnings unheeded by the politicians of a system which was new to industrial society and treated the gods of capitalism with reverence and awe. It swallowed the white lie of Union Carbide’s owners in the United States that the functioning of the Indian plant was completely the outlook of local functionaries and they couldn’t be held accountable. When its honcho arrived in India, he went to a plush guesthouse instead of gallows, his return to New York facilitated by a very own aircraft of Indian government. Warren Anderson, the man, was never served a warrant till he died at the age of 92 in 2014.

Do I ask my listeners or readers to worry if India’s environmental laws are weak or if judiciary dithers all too often, sitting on a judgment for decades before slapping the wrist of six local employees with a fine of $2000 and two-year imprisonment in 2010. Do I tell them to work out how the demand of $3.3 billion as compensation was scaled down to $470 million by the offenders and accepted without a murmur by the affected.

Do I draw their attention to Bhopal Gas Tragedy 2.0 unfolding every living minute since then as the poisonous chemical waste was dumped outside the factory which has contaminated soil and the groundwater, consumed by the poor on its periphery. That scores of deformed lives still use these killing fields as their playground. That no other state finds it politically expedient if the clean-up of the factory and its chemicals are shifted and buried on their turf. That the moneybags who are in possession of these abandoned plants now, another American multinationals Dow Chemicals, sees no reason to spare its dollars and clear the mess or pay up the affected. They, after all, came 17 years onwards the tragedy. Of the assets and liability they have negotiated with the former owners, they are only willing to play ball on assets.

Do I talk about how ruthless capitalism exploited weak nations, importing their technology even when safety legal nets were absent in a vulnerable society? How such a toxic presence was allowed a haven within a heavily populated neighbourhood? How a new nation keen to secure its place in the sun overlooked the cost it could entail on its defenceless?

The only reference I can make with certainty is from history books: Union Carbide played an important role with its chemicals in both the World Wars of the 20th century. After DDT was banned by the United States in 1973, Union Carbide began pushing a highly toxic pesticide, Sevin, for the global agriculture industry battling pests, weeds and viruses. They adopted the template of targeting young nations like India, without a thought to responsible supervision or spending towards its maintenance. India is now wiser by the experience but the Bhopal Gas Tragedy lives on, a trauma it still hasn’t come to grips with.

(This article by the author was published in rt.com).