Around the time when India is saddled with its worst power crisis, political cognoscenti are looking around for Vinod Rai, once chairman of Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India, and on whose decision India discovered a big coal scam.

Once the CAG released its report in 2012-13 and the Supreme Court canceled the coal blocks, the nation plunged into its gravest crisis.

So where is Rai, many are asking?

After a stint with the Board for Control of Cricket in India (BCCI), Rai is now the chairman and Independent non-executive director on the Board of Kalyan Jewellers. He is also an advisor to the Indian Railways, which is asking passengers to get off trains so that tracks could be used for pushing cargo trains carrying coal from mines to power plants.

The Indian government is struggling with the coal crisis, and the resultant power crisis. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has announced, as a part of the stimulus package, that the coal sector would be opened up and coal blocks put up for auction for commercial mining.

“Vinod Rai”effect, anyone?

When the CAG released its report, there were alleged scams all around, no one cared to examine the details. Everyone presumed the CAG must have gone into the details. The CAG said there was a loss of over Rs 1.86 lakh crore in the allocation of coal blocks. Subsequently, the Supreme Court put its stamp on what the CAG had said.

Slowly, India got to know the truth behind the so-called damage that was done. The extent of the ultimate damage is still being debated. Many asked if the CAG computed some wrong numbers while determining the loss to the public exchequer, and more importantly, did the CAG’s actions create an environment where decision-making became even more difficult?

The CAG report had devastating consequences and Rai’s miscalculations have virtually ruined the coal sector. There were hardly any takers for the coal blocks that were auctioned after the first couple of rounds.

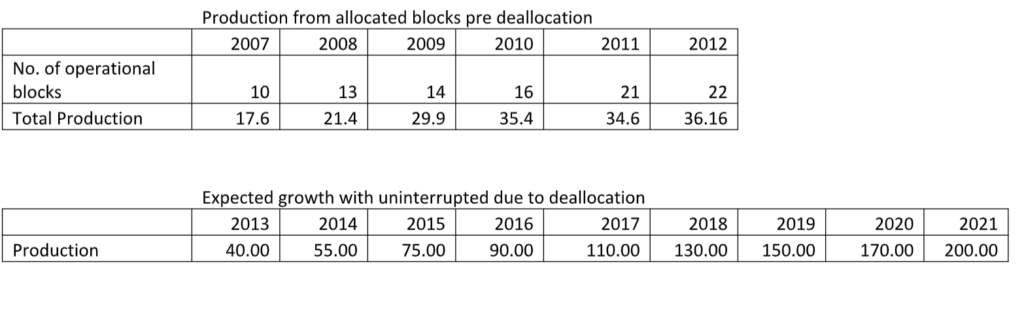

So let’s look at some of the numbers here:

Rai took the convenient method of using averages. He should have gone into the finances of each mine and not launched a fault-finding mission. The impact was devastating on bureaucrats who refrained from committing themselves on the files and played safe.

It was hoped that coal production would increase if the blocks were auctioned. This was not so. In fact, coal production from auctioned mines was well below the estimated amount.

So what is happening in India?

Power plants are running perilously low, there are huge daily power outages in several states. The shortages are sparking scrutiny of India’s long reliance on coal, which produces 70% of the country’s electricity.

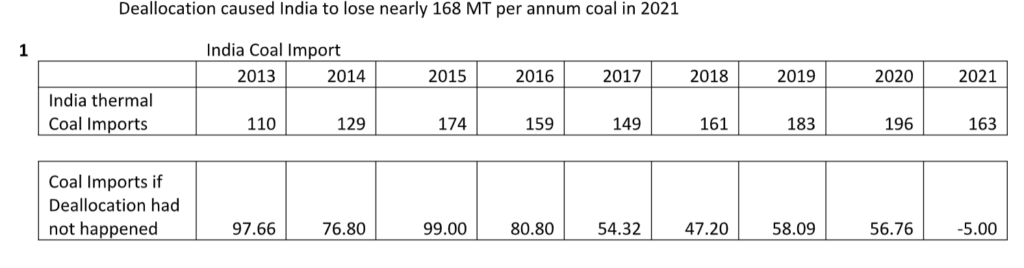

As per the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) data of April 19, 2022, India’s electricity production via thermal plants using domestic coal stood at 182.39 GW with an average of 34 percent coal stock in them. Worse, out of the 173 thermal power plants, 85 plants fired by domestic coal have less than 25 percent stock.

I would offer some more figures here:

The situation highlights India’s pressing need to diversify its energy sources, as demand for electricity is expected to increase more than anywhere else in the world over the next two decades, says the International Energy Agency.

The power shortage is coupled with blistering heat. Schools are closed, there are fires at gigantic landfills and shrivelling crops across the nation reeling under unrelenting heat.

India recorded its hottest March since 1901, and average temperatures in April in northern and central pockets of the country were the highest in 122 years. Temperatures breached 45 degrees Celsius (113 degrees Fahrenheit) in 10 cities last week.

Climate change is making severe temperatures hotter and more frequent, and hurting economic activity, which had been rebounding after pandemic shutdowns, and could disrupt essential services such as hospitals. Many states including Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan are experiencing blackouts of up to seven hours.

The Railways Ministry has canceled more than 750 passenger train services to allow more freight trains to move coal from mines to power plants.

Out of India’s 165 coal plants, 94 are facing critically low coal supplies while 8 are not operational as of Sunday, says the Central Electricity Authority. In short, it means stocks have dropped below 25 percent of normal levels. As per government regulations, power plants must maintain 24 days’ worth of coal stocks, but many routinely don’t. The power outages are less the result of a dearth of coal than inadequate forecasts of demand and plans for transporting it in time.

Imported coal could have helped but global prices have shot up since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, reaching $400 per ton in March, putting it out of reach for cash-strapped power distribution companies.

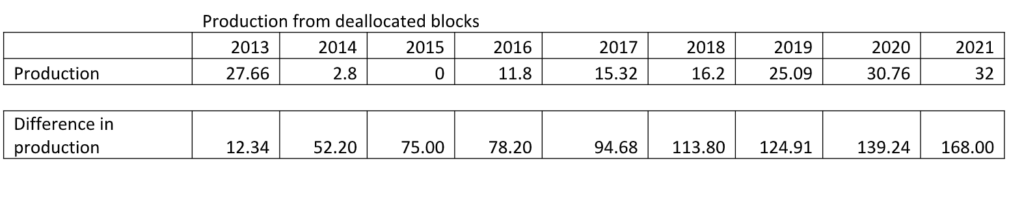

And this is happening when India is among the biggest repositories of coal. And this happened is a story that spans through decades, although accountability for the persisting under-utilisation of domestic coal stocks remains distant. Appeals have gone out from various state governments to the masses to cut back electricity consumption. Easier said than done, especially for industrial units. If deallocation had not happened, the increased coal production could have saved India from the current power crisis by completely supplying the deficit and more.

See the figures below:

Passengers are protesting against the cancellation of trains, especially around the time when the summer holidays are about to start. But the Railway authorities have no other option. With

power plants located across the country, the Railways are forced to run long distance trains.

In 2016-17, 269 coal rakes were loaded by Railways, ramped up in 2017-18 and 2018-19. But during 2019-20 and 2020-21, loading fell to 267 rakes per day. And then in 2021-22, the rakes were increased to 347 per day. And now, it is hovering over 400 rakes per day. For reasons of cost and convenience, rail remains the preferred mode of transport for coal, which generates about 70% of India’s electricity.

In a report, S&P Global Commodity Insights said Indian thermal coal buyers were paying very high prices to import the fuel in what was considered a shift from the traditional pattern of low-cost buying.

Many say the present crisis will finally lead to a reckoning as to how a country with massive coal deposits became among the biggest importers of the critical raw material. Over decades, heads have never rolled, even as imports surge and domestic production crises multiply.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is expected to launch a probe into this, and identify those responsible and when, so that the future may be better than the past has been since coal was nationalised by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in the 1970s in her zeal for government takeover of as much of the economy as possible.

“Domestic stocks border on critical levels amid a surge in summer power demand. Several trades to India for 4,200 kcal/kg GAR coal of Indonesian origin were concluded in the week ending April 29 at $95-$98/mt FOB for Pana- max and Capesize vessels,” the S&P Global Commodity Insights said in a report.

So what does it mean? Miserable times for power plants and consumers, but happy days for coal importers. Data from the Coal Ministry showed the average price for Indonesian thermal coal paid by Indian buyers in 2021 [April-March] was $49.02. It has now more than doubled.

Rajiv Agarwal, secretary general of the Indian Captive Power Producers’ Association said imported coal is coming for NTPC, state-run power plants and general industrial purposes. States like Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh are facing black-outs for over eight hours.

Shailendra Dubey, chairman of All India Power Engineers Federation, an advocacy group, says the crisis is serious. Captive power plants and industry have been getting little or no coal from the Kolkata-based Coal India Limited.

CIL officials did not respond for an immediate comment.

Many industrial units on the verge of closure are buying coal at unviable prices, because a halt in production could trigger industrial unrest. And there are chances of imported goods flooding the markets, perhaps damaging domestic producers for a long time to come.

A looming issue is that of elevated electricity tariffs at the spot power markets. And these raised tariffs have a serious bearing on Indian buyers, who have no choice but to procure costly imported coal.

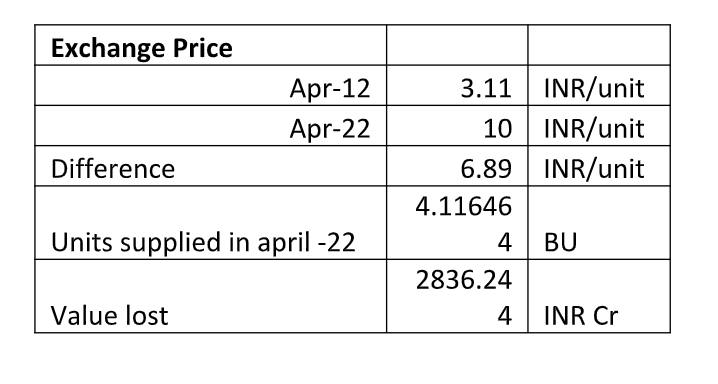

In 2012 when coal production was enough to meet the power demand, exchange prices in April ’12 were at 3.11 INR/unit. Currently in this crisis, the exchange prices in April ’22 have come to around 10 INR/unit. If the coal deallocation had not happened and the coal could have saved India from this crisis, the 4.11 Billion Units sold on exchange could have been sold at the ’12 prices and saved nearly Rs 2836 crores monthly.

Look at the rates. The average price in the spot power markets was Rs 11.85/unit over April 20-28, 2022. Last year, it was Rs 4.39/unit. The electricity supply shortage recorded on April 27, 2022 was 198.51 million units, compared with the shortage of 7.91 million units recorded the same day in 2021.

There is a serious crisis in hand, only if the mines – abandoned by Coal India – had not been closed down by the country’s apex court in its decision on September 24, 2014.

(Award winning author Shantanu Guha Ray’s book, Black Harvest: India’s Untold Coal Story will hit the stands soon.)

(Shantanu Guha Ray is a Wharton-trained journalist and award-winning author. He lives in Delhi with his wife and two pets. He won the 2018 Crossword award for his book, Target, which probed the NSEL payment crisis.)